Programming totally with head and tail

How can we turn the infamous head and tail partial functions into total

functions? You may already be acquainted with two common solutions.

Today, we will investigate a more exotic answer using dependent types.

The meat of this post will be written in Agda, but should look familiar enough to Haskellers to be an accessible illustration of dependent types.

Background

The list functions head and tail are frowned upon because they are partial

functions: if they are applied to the empty list, they will blow up and

break your program.

head :: [a] -> a

head (x : _) = x

head [] = error "empty list"

tail :: [a] -> [a]

tail (_ : xs) = xs

tail [] = error "empty list"Sometimes we know that a certain list is never empty.

For example, if two lists have the same length, then after pattern-matching

on one, we also know the constructor at the head of the other.

Or the list is hard coded in the source for some reason, so we can see right

there that it’s not empty.

In those cases, isn’t it safe to use head and tail?

Rather than argue that unsafe functions are safe to use in a particular

situation (and sometimes getting it wrong), it is easier to side-step the

question altogether and replace head and tail with safer idioms.

To start, directly pattern-matching on the list is certainly a fine alternative.

Just short of that, one variant of head and tail wraps the result in

Maybe so we can return Nothing in error cases, to be unpacked with whatever

error-handling mechanism is available at call sites.

headMaybe :: [a] -> Maybe a

tailMaybe :: [a] -> Maybe [a]Another variant changes the argument type to be the type of non-empty lists, thus requiring callers to give static evidence that a list is not empty.

-- Data.List.NonEmpty

data NonEmpty a = a :| [a]

headNonEmpty :: NonEmpty a -> a

tailNonEmpty :: NonEmpty a -> [a]In this post, I’d like to talk about one more total version of head and

tail.

headTotal and tailTotal

Example

From now on, let us surreptitiously switch languages to Agda (syntactically

speaking, the most disruptive change is swapping the roles of : and ::).

The functions headTotal and tailTotal are funny because they

make the following examples well-typed:

headTotal (1 ∷ 2 ∷ 3 ∷ []) : Nat

tailTotal (1 ∷ 2 ∷ 3 ∷ []) : List NatUnlike

headMaybe, the result has typeNat, notMaybe Nat.Unlike

headNonEmpty, the input list1 ∷ 2 ∷ 3 ∷ []has typeList Nat, a plain list, notNonEmpty—orList⁺as it is cutely named in Agda.

headTotal and tailTotal will be defined in Agda, so they are most

definitely total.

And yet they appear to be as convenient to use as the partial head and

tail, where they can just be applied to a non-empty list to access its head

and tail.

As you might have noticed, this post is an advertisement for dependent types,

which are the key ingredients in the making of headTotal and tailTotal.

Naturally, this example only demonstrates the good points of these functions; we’ll get to the less good ones in time.

Let the types take the wheel

Let’s find the type and the body of headTotal.

We put question marks as placeholders to be filled incrementally.

headTotal : ?

headTotal = ?Obviously the type is going to depend on the input list. To define that dependent type, we will declare one more function to be refined simultaneously.

headTotal is a function parameterized by a type a and a list

xs : List a, and with return type headTotalType xs,

which is another function of xs.

That tells us to add some quantifiers and arrows to the type annotations.

headTotalType : ∀ {a : Set} (xs : List a) → ?

headTotalType = ?

headTotal : ∀ {a : Set} (xs : List a) → headTotalType xs

headTotal = ?(Note: Set is the “type of types” in Agda, called Type in Haskell.)

headTotalType must return a type, i.e., a Set.

Put that to the right of headTotalType’s arrow.

A function producing a type is also called a type family:

a family of types indexed by lists xs : List a.

headTotalType : ∀ {a : Set} (xs : List a) → Set

headTotalType = ?

headTotal : ∀ {a : Set} (xs : List a) → headTotalType xs

headTotal = ?Pattern-match on the list xs, splitting both functions into two cases.

headTotalType : ∀ {a : Set} (xs : List a) → Set

headTotalType (x ∷ xs) = ?

headTotalType [] = ?

headTotal : ∀ {a : Set} (xs : List a) → headTotalType xs

headTotal (x ∷ xs) = ?

headTotal [] = ?In the non-empty case (x ∷ xs), we know the head of the list is x, of type

a. Therefore that case is solved.

headTotalType : ∀ {a : Set} (xs : List a) → Set

headTotalType (_ ∷ _) = a

headTotalType [] = ?

headTotal : ∀ {a : Set} (xs : List a) → headTotalType xs

headTotal (x ∷ _) = x

headTotal [] = ?What about the empty case? We are looking for two values headTotalType []

and headTotal [] such that the former is the type of the latter:

headTotal [] : headTotalType []That tells us that the type headTotalType [] is inhabited.

What else can we say about those unknowns?

…

After much thought, there doesn’t appear to be any requirement besides the

inhabitation of headTotalType [].

Then, a noncommittal solution is to instantiate it with the unit type,

avoiding the arbitrariness in subsequently choosing its inhabitant,

since there is only one.

The unit type and its unique inhabitant are denoted tt : ⊤ in Agda.

headTotalType : ∀ {a : Set} (xs : List a) → Set

headTotalType (_ ∷ _) = a

headTotalType [] = ⊤ -- unit type

headTotal : ∀ {a : Set} (xs : List a) → headTotalType xs

headTotal (x ∷ _) = x

headTotal [] = tt -- unit valueTo recapitulate that last case,

when the list is empty, there is no head to take,

but we must still produce something.

Having no more requirements, we produce a boring thing, which is tt.

The definition of headTotal is now complete.

Following similar steps, we can also define tailTotal.

tailTotalType : ∀ {a : Set} (xs : List a) → Set

tailTotalType (_ ∷ _) = List a

tailTotalType [] = ⊤

tailTotal : ∀ {a : Set} (xs : List a) → tailTotalType xs

tailTotal (_ ∷ xs) = xs

tailTotal [] = ttAnd with that, we can finally build the examples above!

some_number : Nat

some_number = headTotal (1 ∷ 2 ∷ 3 ∷ [])

some_list : List Nat

some_list = tailTotal (1 ∷ 2 ∷ 3 ∷ [])We’re pretty much done, but we can still refactor a little to make this nicer to look at.

More polishing

First, notice that the two type families

headTotalType and tailTotalType are extremely similar, differing

only on whether the ∷ case equals a or List a.

Let’s merge them into a single function:

we define a type b `ifNotEmpty` xs,

equal to b if xs is not empty, otherwise equal to ⊤.

_`ifNotEmpty`_ : ∀ {a : Set} (b : Set) (xs : List a) → Set

b `ifNotEmpty` (_ ∷ _) = b

_ `ifNotEmpty` [] = ⊤

headTotal : ∀ {a : Set} (xs : List a) → a `ifNotEmpty` xs

tailTotal : ∀ {a : Set} (xs : List a) → List a `ifNotEmpty` xsThe infix notation reflects the intuition that headTotal has a meaning close

to a function List a → a, and similarly with tailTotal.

Finally, one last improvement is to reconsider the intention behind the unit

type ⊤ in this definition. If headTotal or tailTotal are applied to an

empty list, we probably messed up somewhere.

Such mistakes are made easier to spot by replacing ⊤ with an isomorphic but

more appropriately named type. If an empty list causes an error, we will either

see a Failure to unify, or some ERROR screaming at us.

data Failure : Set where

ERROR : Failure

_`ifNotEmpty`_ : ∀ {a : Set} (b : Set) (xs : List a) → Set

b `ifNotEmpty` (_ ∷ _) = b

b `ifNotEmpty` [] = Failure

headTotal : ∀ {a} (xs : List a) → a `ifNotEmpty` xs

headTotal (x ∷ _) = x

headTotal [] = ERROR

tailTotal : ∀ {a} (xs : List a) → List a `ifNotEmpty` xs

tailTotal (_ ∷ xs) = xs

tailTotal [] = ERRORWe’ve now come full circle. The bodies of headTotal and tailTotal closely

resemble those of the partial head and tail functions at the beginning of

this post.

The difference is that dependent types keep track of the erroneous cases.

A working Agda module with these functions can be found in the source repository of this blog. There is also a version in Coq.

(This was my first time programming in Agda. This language is super smooth.)

Ergonomics and applications

One might question how useful headTotal and tailTotal really are.

They may be not so different from headNonEmpty and tailNonEmpty,

because they’re all only meaningful with non-empty lists: the burden of proof

is the same. Even if we added ERROR values to cover the [] case, the point

is really to not ever run into that case.

Moreover, to actually get the head out, headTotal requires its argument to

be definitionally non-empty, otherwise the ergonomics are not much better than

headMaybe.

In other words, for headTotal e to have type a rather than

a `ifNotEmpty` e, the argument e must actually be an expression

which reduces to a non-empty list e1 :: e2, but that literally gives us an

expression e1 for the head of the list. Why not use it directly?

The catch is that the expression for the head might be significantly more

complex than the expression for the list itself, so we’d still rather write

headTotal e than whatever that reduces to.

For example, I’ve used a variation of this technique in a type-safe

implementation of printf.1

The function printf takes a format string as its first argument,

basically a string with holes.

For instance, "%s du %s" is a format string with two placeholders for

strings.

Then, printf expects more arguments to fill in the holes.

Once supplied, the result is a string with the holes correspondingly filled.

Importantly, format strings may vary in number and types of holes.

printf "%s du %s" "omelette" "fromage" ≡ "omelette du fromage"

printf "%d * %d = %d" 6 9 42 ≡ "6 * 9 = 42"Intuitively, that means the type of printf depends on the format string:

printf : ∀ (fmt : string) → printfType fmt

printfType : string → SetHowever, not all strings are valid format strings.

If a special character is misused, for example,

printf may evaluate to ERROR.2

printf "%m" = ERROR -- "%m" makes no sense

printfType "%m" = FailureIn all “correct” programs, printf is meant to be used with valid and

statically known format strings, so the ERROR case doesn’t happen.

Nevertheless, printf "%d * %d = %d" is a simpler expression to write than

whatever it evaluates to, which would be some lambda that serializes its three

arguments according to that format string.

I don’t have more examples right now, but this dependently typed validation technique seems well-suited to more general kinds of compile-time configurations, where it would not be practical to define a type encoding the necessary invariants.

Another hypothetical use case would be to extract the output of some

parameterized search algorithm.

Let’s imagine that it may not find a solution in general, so its return type

should be a possibly empty List a. If you know that it does output something

for some hard-coded parameters, then headTotal allows you to access it with

little ceremony.

On a related note, ifNotEmpty seems generalizable to a dependently typed

variant of the Maybe monad, keeping track of all the conditions for it to not

be a Failure at the type level.

Conclusion

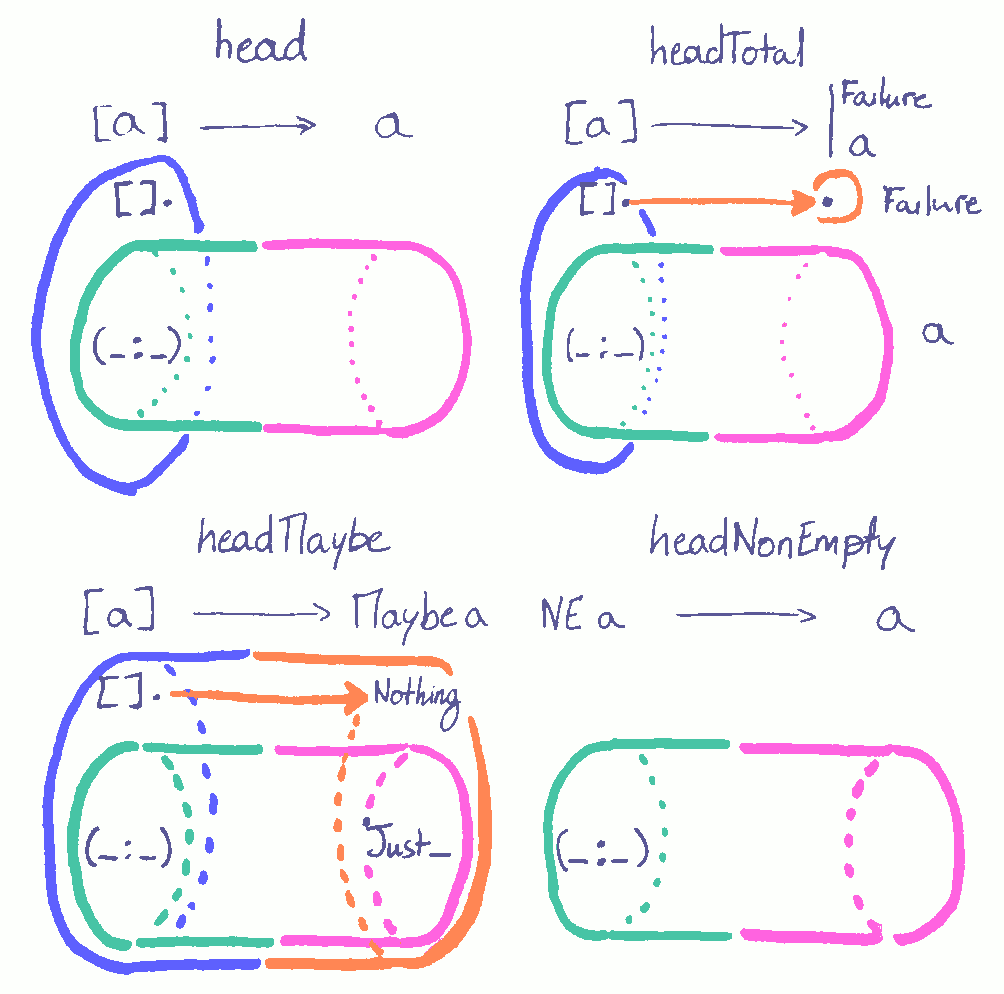

head featured here.

headis partial, undefined at[].headTotalmaps into two types,Failureanda, depending on the value of the input.headMaybemaps intoMaybe a, a bigger type thana, and cuttingaout of it would take a bit of work.headNonEmptyhas the cleanest looking diagram from putting the problem of[]out of scope.

What other variations are there?

coq-printf. This trick is no longer used since version 2.0.0 though, a better alternative having been found in Coq’s new system for string notations.↩︎

It would also be reasonable to ignore the “error” and accept all strings as valid.↩︎