The pro-PER meaning of "proper"

A convenient proof tactic is to rewrite expressions using a relation other

than equality. Some setup is required to ensure that such a proof step is allowed.

One important obligation is to prove Proper theorems for the various functions

in our library. For example, a theorem like

#[global]

Instance Proper_f : Proper ((==) ==> (==)) f.

unfolds to forall x y, x == y -> f x == f y, meaning that f preserves some relation (==),

so that we can “rewrite x into y under f”. Such a theorem must be registered as an

instance so that the rewrite tactic can find it via type class search.

Where does the word “proper” come from?

How does Proper ((==) ==> (==)) f unfold to forall x y, x == y -> f x == f y?

You can certainly unfold the Coq definitions of Proper and ==> and voilà,

but it’s probably more fun to tell a proper story.

It’s a story in two parts:

- Partial equivalence relations

- Respectfulness

Some of the theorems discussed in this post are formalized in this snippet of Coq.

Partial equivalence relations (PERs)

Partial equivalence relations are equivalence relations that are partial. 🤔

In an equivalence relation, every element is at least related to itself by reflexivity. In a partial equivalence relation, some elements are not related to any element, not even themselves. Formally, we simply drop the reflexivity property: a partial equivalence relation (aka. PER) is a symmetric and transitive relation.

Class PER (R : A -> A -> Prop) :=

{ PER_symmetry : forall x y, R x y -> R y x

; PER_transitivity : forall x y z, R x y -> R y z -> R x z }.

We may remark that an equivalence relation is technically a “total” partial equivalence relation.

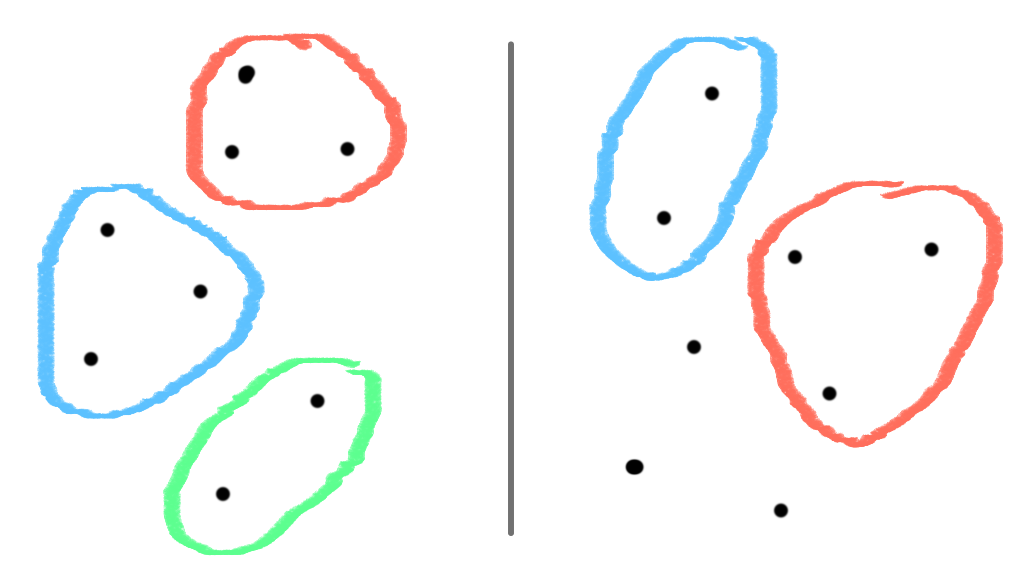

An equivalent way to think about an equivalence relation on a set is as a partition of that set into equivalence classes, such that elements in the same class are related to each other while elements of different classes are unrelated. Similarly, a PER can be thought of as equivalence classes that only partially cover a set: some elements may belong to no equivalence class.

On the right, a partial partition representing a PER.

Exercise: define the equivalence classes of a PER; show that they are disjoint.

Solution

The equivalence classes of a PER R : A -> A -> Prop

are sets of the form C x = { y ∈ A | R x y }.

Given two equivalence classes C x and C x', we show that these sets are

either equal or disjoint. By excluded middle:

Either

R x x', thenR x y -> R x' yby symmetry and transitivity, soy ∈ C x -> y ∈ C x', and the converse by the same argument. ThereforeC x = C x'.Or

~ R x x', then we show that~ (R x y /\ R x' y):- assume

R x yandR x' y, - then

R x x'by symmetry and transitivity, - by

~ R x x', contradiction.

Hence,

~ (y ∈ C x /\ y ∈ C x'), thereforeC xandC x'are disjoint.- assume

(I wouldn’t recommend trying to formalize this in Coq, because equivalence classes are squarely a set-theoretic concept. We just learn to talk about things differently in type theory.)

A setoid is a set equipped with an equivalence relation. A partial setoid is a set equipped with a PER.

PERs are useful when we have to work in a set that is “too big”.

A common example is the set of functions on some setoid.

For instance, consider the smallest equivalence relation (≈) on three elements

{X, X', Y} such that X ≈ X'.

Intuitively, we want to think of X and X' as “the same”, so that the set

morally looks like a two-element set.

How many functions {X, X', Y} -> {X, X', Y} are there? If we ignore the

equivalence relation, then there are 33 functions. But if we think

of {X, X', Y} as a two-element set by identifying X and X', there should

be 22 functions.

The actual set of functions {X, X', Y} -> {X, X', Y} is “too big”:

it contains some “bad” functions which break the illusion that

XandX'are the same, for example by mappingXtoXandX'toY;(* A bad function *) bad X = X bad X' = Y bad Y = Yit contains some “duplicate” functions, for example the constant functions

const Xandconst X'should be considered the same sinceX ≈ X'.

To tame that set of functions, we equip it with the PER R where

R f g if forall x y, x ≈ y -> f x ≈ g y.

Definition R f g : Prop := forall x y, x ≈ y -> f x ≈ g y.

That relation R has the following nice features:

Bad functions are not related to anything:

forall f, not (R bad f).Duplicate functions are related to each other:

R (const X) (const X').

Having defined a suitable PER, we now know to ignore the “bad” unrelated elements and to identify elements related to each other. Those remaining “good” elements are called the proper elements.

A proper element x of a relation R is one that is related to itself: R x x.

This is how the Proper class is defined in Coq:

(* In the standard library: From Coq Require Import Morphisms *)

Class Proper {A} (R : A -> A -> Prop) (x : A) : Prop :=

proper_prf : R x x.

Note that properness is a notion defined for any relation, not only PERs. This story could probably be told more generally. But I think PERs make the motivation more concrete, illustrating how relations let us not only relate elements together, but also weed out badly behaved elements via the notion of properness.

The restriction of a relation R to its proper elements is reflexive.

Hence, if R is a PER, its restriction is an equivalence relation.

In other words, a PER is really an equivalence relation with an oversized

carrier.

Exercise: check that there are only 4 functions {X, X', Y} -> {X, X', Y}

if we ignore the non-proper functions and we equate functions related to each

other by R.

Solution

The equivalence classes are listed in the following table, one per row, with

each sub-row giving the mappings of one function for X, X', Y. There are

4 equivalence classes spanning 15 functions, and 12 “bad” functions that don’t

belong to any equivalence classes.

X X' Y

------------------

1 X X X 1

X X X' 2

X X' X 3

X X' X' 4

X' X X 5

X' X X' 6

X' X' X 7

X' X' X' 8

------------------

2 X X Y 9

X X' Y 10

X' X Y 11

X' X' Y 12

------------------

3 Y Y X 13

Y Y X' 14

------------------

4 Y Y Y 15

------------------

Bad X Y X 16

X Y X' 17

X' Y X 18

X' Y X' 19

X Y Y 20

X' Y Y 21

Y X X 22

Y X X' 23

Y X' X 24

Y X' X' 25

Y X Y 26

Y X' Y 27

Exercise: given a PER R, prove that an element is related to itself by R

if and only if it is related to some element.

Theorem Prim_and_Proper {A} (R : A -> A -> Prop) :

PER R ->

forall x, (R x x <-> exists y, R x y).

(Solution)

Respectfulness

The relation R defined above for functions {X, X', Y} -> {X, X', Y}

is an instance of a general construction. Given two sets D and C,

equipped with relations RD : D -> D -> Prop and RC : C -> C -> Prop

(not necessarily equivalences or PERs), two functions f, g : D -> C

are respectful if they map related elements to related elements.

Thus, respectfulness is a relation on functions, D -> C, parameterized by

relations on their domain D and codomain C:

(* In the standard library: From Coq Require Import Morphisms *)

Definition respectful {D} (RD : D -> D -> Prop)

{C} (RC : C -> C -> Prop)

(f g : D -> C) : Prop :=

forall x y, RD x y -> RC (f x) (g y).

(Source)

The respectfulness relation is also cutely denoted using (==>), viewing it as

a binary operator on relations.

Notation "f ==> g" := (respectful f g) (right associativity, at level 55)

: signature_scope.

(Source)

For example, this lets us concisely equip a set of curried functions

E -> D -> C with the relation RE ==> RD ==> RC.

Respectfulness provides a point-free notation to construct relations on

functions.

(RE ==> RD ==> RC) f g

<->

forall s t x y, RE s t -> RD x y -> RC (f s x) (g t y)

Respectfulness on D -> C can be defined for any relations on D and C.

Two special cases are notable:

If

RDandRCare PERs, thenRD ==> RCis a PER onD -> C(proof), so this provides a concise definition of extensional equality on functions (This was the case in the example above.)If

RDandRCare preorders (reflexive, transitive), then the proper elements ofRD ==> RCare exactly the monotone functions.

Proper respectful functions and rewriting

Now consider the proper elements of a respectfulness relation. Recalling the earlier definition of properness, it transforms a (binary) relation into a (unary) predicate:

Proper : (A -> A -> Prop) -> (A -> Prop)

While we defined respectfulness as a binary relation above, we shall also say

that a single function f is respectful when it maps related elements to

related elements. The following formulations are equivalent; in fact, they are

all the same proposition by definition:

forall x y, RD x y -> RC (f x) (f y)

=

respectful RD RC f f

=

(RD ==> RC) f f

=

Proper (RD ==> RC) f

The properness of a function f with respect to the respectfulness relation

RD ==> RC is exactly what we need for rewriting. We can view f as

a “context” under which we are allowed to rewrite its arguments along the

domain’s relation RD, provided that f itself is surrounded by a context

that allows rewriting along the codomain’s relation RC.

In a proof, the goal may be some proposition in which f x occurs, P (f x),

then we may rewrite that goal into P (f y) using an assumption RD x y,

provided that Proper (RD ==> RC) f and Proper (RC ==> iff) P,

where iff is logical equivalence, with the infix notation <->.

Definition iff (P Q : Prop) : Prop := (P -> Q) /\ (Q -> P).

Notation "P <-> Q" := (iff P Q).

Respectful functions compose:

Proper (RD ==> iff) (fun x => P (f x))

=

forall x y, RD x y -> P (f x) <-> P (f y)

And that, my friends, is the story of how the concept of “properness” relates to the proof technique of generalized rewriting.

Appendix: Pointwise relation

Another general construction of relations on functions is the “pointwise

relation”. It only assumes a relation on the codomain RC : C -> C -> Prop.

Two functions f, g : D -> C are related pointwise by RC if

they map each element to related elements.

(* In the standard library: From Coq Require Import Morphisms *)

(* The domain D is not implicit in the standard library. *)

Definition pointwise_relation {D C} (RC : C -> C -> Prop)

(f g : D -> C) : Prop :=

forall x, RC (f x) (g x).

(* Abbreviation (not in the stdlib) *)

Notation pr := pointwise_relation.

(Source)

This is certainly a simpler definition: pointwise_relation RC

is equivalent to eq ==> RC, where eq is the standard intensional equality

relation.

One useful property is that pointwise_relation RC is an equivalence relation

if RC is an equivalence relation.

In comparison, we can at most say that RD ==> RC is a PER if RD and

RC are equivalence relations. It is not reflexive as soon as RD is bigger

than eq (the smallest equivalence relation) and RC is smaller than the total

relation fun _ _ => True.

In Coq, the pointwise_relation is also used for rewriting under lambda

abstractions. Given a higher-order function f : (E -> F) -> D,

we may want to rewrite f (fun z => M z) to f (fun z => N z),

using a relation forall z, RF (M z) (N z), where the function bodies M

and/or N depend on z so the universal quantification is necessary to bind

z in the relation. This can be done using the setoid_rewrite tactic,

after having proved a Proper theorem featuring pointwise_relation:

#[global]

Instance Proper_f : Proper (pointwise_relation RF ==> RD) f.

One disadvantage of pointwise_relation is that it is not compositional.

For instance, it is not preserved by function composition:

Definition compose {E D C} (f : D -> C) (g : E -> D) : E -> C :=

fun x => f (g x).

Theorem not_Proper_compose :

not

(forall {E D C}

(RD : D -> D -> Prop) (RC : C -> C -> Prop),

Proper (pr RC ==> pr RD ==> pr RC)

(compose (E := E))).

Instead, at least the first domain of compose should be quotiented by RD ==> RC instead:

#[global]

Instance Proper_compose {E D C}

(RD : D -> D -> Prop) (RC : C -> C -> Prop) :

Proper ((RD ==> RC) ==> pr RD ==> pr RC)

(compose (E := E)).

We can even use ==> everywhere for a nicer-looking theorem:

#[global]

Instance Proper_compose' {E D C} (RE : E -> E -> Prop)

(RD : D -> D -> Prop) (RC : C -> C -> Prop) :

Proper ((RD ==> RC) ==> (RE ==> RD) ==> (RE ==> RC))

compose.

Exercise: under what assumptions on relations RD and RC do

pointwise_relation RD and RC ==> RD coincide on the set of proper elements

of RC ==> RD?

Solution

Theorem pointwise_respectful {D C} (RD : D -> D -> Prop) (RC : C -> C -> Prop)

: Reflexive RD -> Transitive RC ->

forall f g, Proper (RD ==> RC) f -> Proper (RD ==> RC) g ->

pointwise_relation RC f g <-> (RD ==> RC) f g.

This table summarizes the above comparison:

pointwise_relation |

respectful (==>) |

|

|---|---|---|

| is an equivalence | yes | no |

| allows rewriting under binders | yes | no |

| respected by function composition | no | yes |

Appendix: Parametricity

Respectfulness lets us describe relations RD ==> RC on functions

using a notation that imitates the underlying type D -> C.

More than a cute coincidence, this turns out to be a key component of

Reynolds’s interpretation of types as relations:

==> is the relational interpretation of the function type constructor ->.

Building upon that interpretation, we obtain free theorems to

harness the power of parametric polymorphism.

Free theorems provide useful properties for all polymorphic functions of

a given type, regardless of their implementation. The canonical example is the

polymorphic identity type ID := forall A, A -> A. A literal reading of that

type is that, well, for every type A we get a function A -> A. But this

type tells us something more: A is abstract to the function, it cannot

inspect A, so the only possible implementation is really the identity

function fun A (x : A) => x. Free theorems formalize that intuition.

The type ID := forall A, A -> A is interpreted as the following relation

RID:

Definition RID (f g : forall A, A -> A) : Prop :=

forall A (RA : A -> A -> Prop), (RA ==> RA) (f A) (g A).

where we translated forall A, to forall A RA, and A -> A to RA ==> RA.

The parametricity theorem says that every typed term t : T

denotes a proper element of the corresponding relation RT : T -> T -> Prop,

i.e., RT t t holds. “For all t : T, RT t t” is the “free theorem”

for the type T.

The free theorem for ID says that any function f : ID satisfies RID f f.

Unfold definitions:

RID f f

=

forall A (RA : A -> A -> Prop) x y, RA x y -> RA (f A x) (f A y)Now let z : A be an arbitrary element of an arbitrary type,

and let RA := fun x _ => x = z. Then the free theorem instantiates to

x = z -> f A x = zEquivalently,

f A z = zthat says exactly that f is extensionally equal to the identity function.

More reading

A New Look at Generalized Rewriting in Type Theory, Mathieu Sozeau, JFR 2009

R E S P E C T - Find Out What It Means To The Coq Standard Library, Lucas Silver, PLClub blog 2020